Risk identification

To identify risks is to look for, imagine, and dig up potential problems and then put them on a list. Risk identification does not need to be more complicated.

To identify risks is to look for, imagine, and dig up potential problems and then put them on a list. Risk identification does not need to be more complicated. At this stage of the process more is definitely better; later less will be more. Lawyers refer to this process as "issue spotting." The objective is to brainstorm risks.

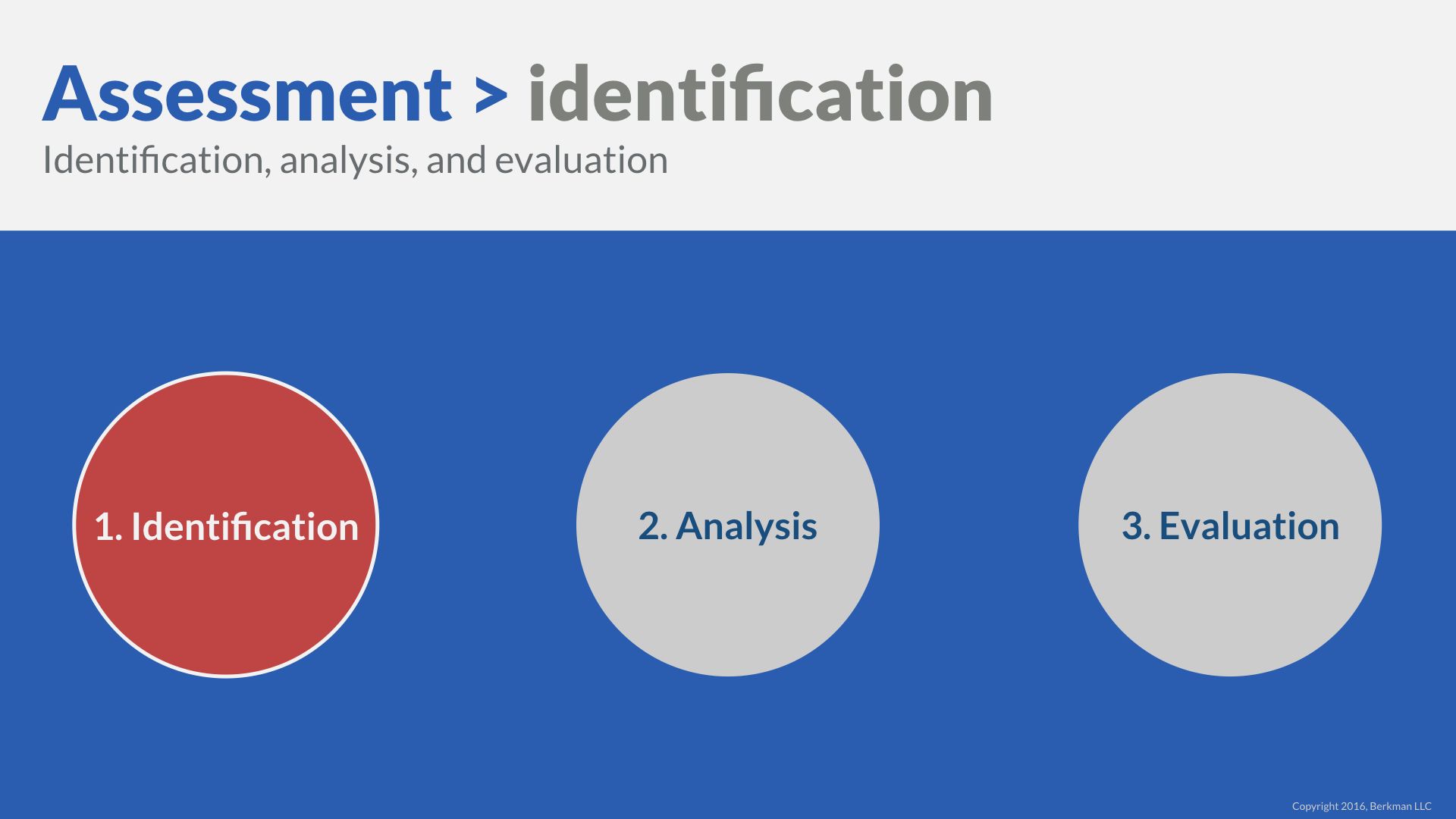

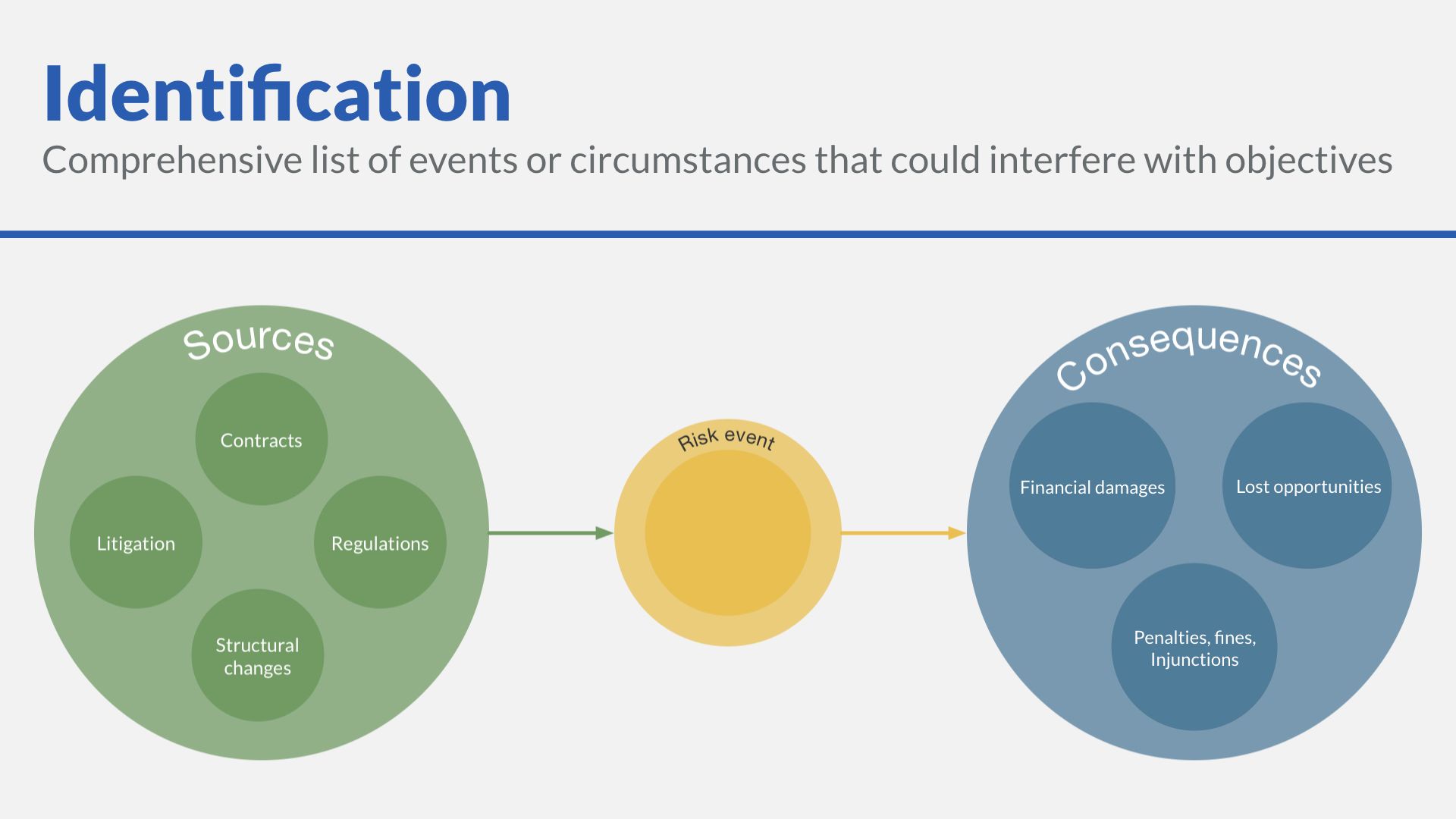

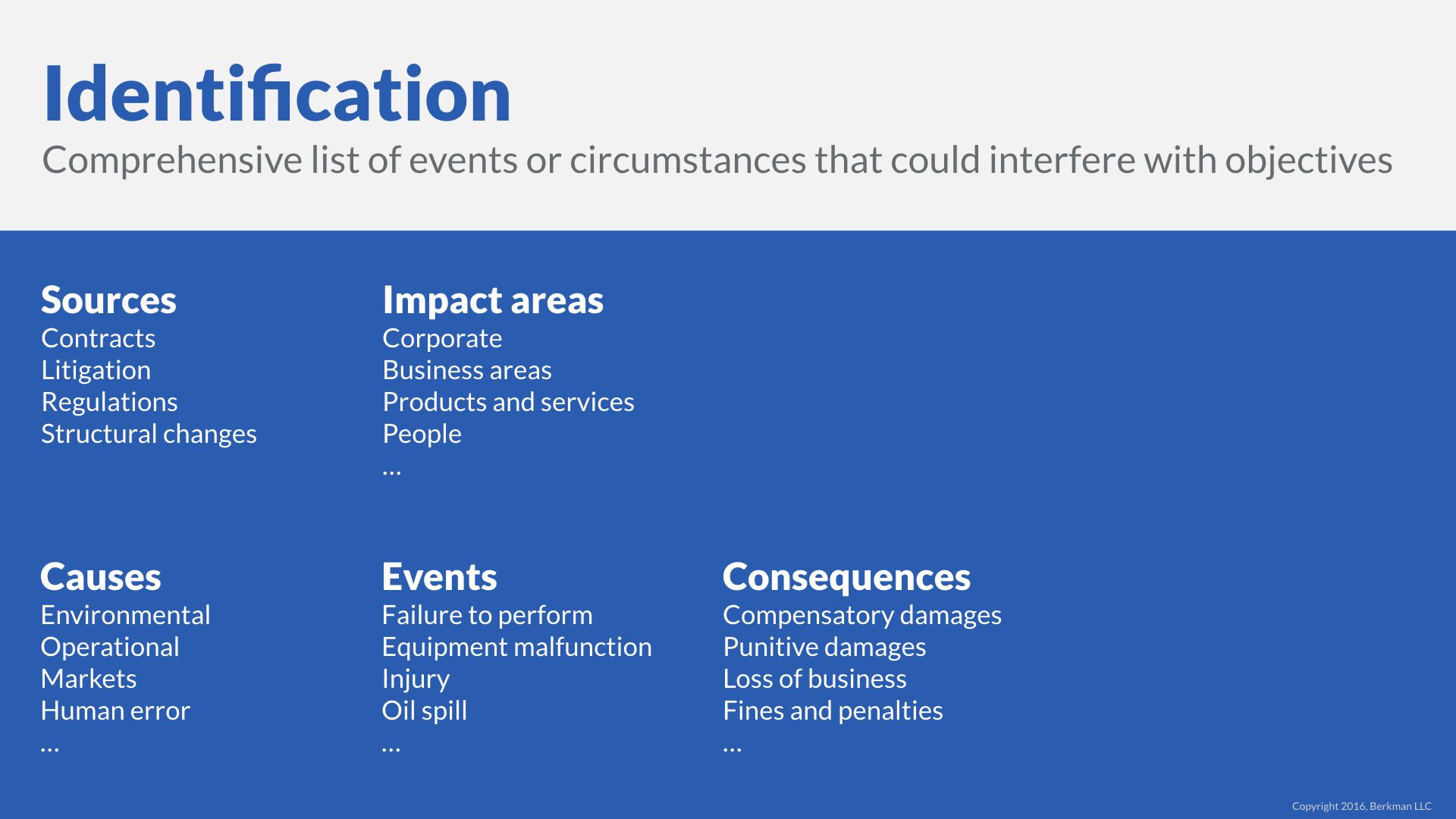

Risk identification means a comprehensive list of events or circumstances that could interfere with objectives.

Generate ideas for risk identification

By whatever name, the risk identification process is ideally collaborative and comprehensive. Comprehensive in this case means that each type of legal risk makes the list regardless of whether the event, process, or practice giving rise to the risk has occurred. The implication is that identifying potential or imaginary risks is acceptable, even, encouraged.

Breadth over depth. With risk identification it is more important to capture an idea than it is to pare the list. That will come later.

It is tempting to reject risks as inconsequential or highly unlikely before even adding them to the risk registry. The better approach is to capture the risk and then rate it with our lowest likelihood and consequences rating as appropriate.

That’s fine, but for those of us that are not very imaginative, how do we generate a list of risks to even consider? Of course it depends on the nature of our organization, where we are located, and the industry in which we operate.

First, let’s remind ourselves of the direction of legal risk:

- Legal sources can lead to non-legal consequences through a risk event.

- Or we can flip that relationship around, so non-legal sources have legal consequences.

And yes, knock on or derivative effects can add depth to our chart.

Here are some broad topic areas to help us generate ideas to identify legal risks.

Legal sources is the easiest place to start. Try asking the following questions:

- Which contract or contracts make up a meaningful share of our revenue? That question leads to the following risk: “Breach of Contract ABC.”

- Do recent intellectual property claims in our industry apply to our products or services? This question leads us to add the risk: “Patent litigation over XZY business process.”

- What changes in regulatory policy in our industry have occurred in the last year? This question might lead us to identify a positive risk like, “Decrease in permit application time,” or a negative risk like, “Increase in enforcement activity.”

When we look at ** Impact areas** we ask: - What about our corporate structure or practices give risk to legal risks? Maybe an unusual corporate form make it a challenge raise additional capital.

- We divisions or units have unique legal risks? A division might offer indemnification on a regular basis to help close business.

- Do products create product liability risks? Does a service business trigger special licensing requirements?

- Are there managers who have a pattern of complaints that might escalate?

When we flip the causes and consequences, we can uncover additional risks: - What activities create environmental risks that might lead to litigation risk?

- What operations are prone to injuring works? What information technology practices create a risk of cyber attack or breach of private data? These give rise to both regulatory and litigation risks.

We can ask if there are events that generate risks.

Finally, we can start with the consequences and ask “under what conditions, are we exposed to punitive damages claims or regulatory fines? The answers allow us to identify risks.

These topics are not meant to be exhaustive. They are only meant to inspire risk identification. The external and internal context of your organization must shape where you look for risks.

Identification > dependencies

Risk identification depends on the data and people available to us. Risk identification is not an ivory tower, solo exercise. It is, instead, an interactive and dynamic process where we explore data about the organization.

What sort of data? I thought we said that legal risk assessments were “qualitative” not quantitative. That is true, but data is still a vital part of a qualitative risk assessment. Remember, the difference is that data informs and improves an expert judgement about a risk factor. We are not talking about data for a statistical or predictive model.

It is not unusual for legal professional to be unaware of basic, important organizational facts, like:

- Which product or service contributes the most EBITDA (or whatever profit measure your organization uses) to the organization?

- Which division, subsidiary, or group is growing the fastest?

- What are the compensation drivers of senior management (revenue growth, profitability, or something else)?

- How many transactions does the organization complete in a week, month, or year?

- What are the revenue recognition rules for the organization?

These types of facts can quickly reveal sources of risk and put others in perspective.

People are also important to the risk identification process. Staff and management throughout the organization can provide vital input to identify risks.

Imagine, for example, that one of the corporate attorneys, Jonathan, attends a cybersecurity continuing legal education (CLE) class. In that class, he hears a presenter say that the leading provider of document databases (also called “nosql” databases) does not encrypt data to help boost performance.

Upon his return to the office, the corporate lawyers, thinking he has spotted a risk, directs the company to stop using in and all nosql databases from this provider. This directive in isolation is potentially damaging to the company.

If, however, he collaborates with Jane, the head of information technology company, the risk identification is quite different. Jane tells him that only the default setting for encryption is set to off. Their business practice is set to on (this is a “risk control”).

Jonathan and Jane collaborate to identify two potential risks:

- Implementations of this provider where the encryption settings are incorrectly configured (failure of risk control), and

- Any other nosql providers in use where the encryption settings have not been reviewed.

Notice that both of these risks entail a lot of uncertainty. They don’t even know if there are any such databases. They don’t know whether the type of data is consequential in the event of a breach. They also don’t know about the likelihood of a breach.

One ill-formed reaction transformed into two clear risks worthy of analysis.

Identification process

We collaborate with other people in the organization and we go find some useful data. How does risk identification actually happen? What are the specific techniques to identify risks?

Yes.

There are quite a few, but we will call out eight techniques:

- Brainstorming can be more or less formal. Brainstorming sessions can vary widely in quality based on a variety of factors. They best when facilitated by an experienced facilitator knowledgeable about legal risk.

- Interviews are more formal than brainstorm. The person charged with risk identification questions those knowledge about the domain to extract information inputs for the risk process.

- Checklists are useful for identifying routine risks. There is a risk with any method that the method itself generates risks. A checklist, for example, can causes us to overlook risks outside the four corners of the checklist. In many cases the checklist is an excellent way to codify our risk identification process.

- Scenario analysis is a technique that is familiar in substance, if not in name, to most legal professionals. Here we ask “what if?” Scenario analysis is particular useful for articulating permutations of an event.

- The Delphi technique is one we will explore in the Techniques section in a little more detail. It is traditionally a more structured version of brainstorming among experts that allows for anonymous expert opinions that are available to other experts in the group.

- Cause and effect at the identification phase allows us to spot derivative or follow on consequences. Each link in the causation chain can also help with scenario analysis by asking what if a different effect happened.

- SWIFT is a structured, team based approach to identify risks.

- Throughout this course so far, we have leaned heavily on the Likelihood and Consequences Matrix to identify risks.

There are many other techniques to identify risks. The culture of each teams and organization influences whether a particular technique works well or not.

Whatever technique we use, risk identification is about open and honest generation of potential risks.

Identification > outcome

So we have identified a bunch of legal risks. What do we do with them? We begin a risk registry.

A risk registry is a list of our legal risks. It will become a bit more, but for now a list of all our legal risks is a giant step in the evolution toward a well managed organization.

What goes in the risk registry?

- A short title for the risk event

- A description of the risk

- The preliminary likelihood rating even if the rating is unknown

- The preliminary consequences rating even if the rating is unknown

- The type of legal risk: contact, litigation, regulatory, or structural

- The level of uncertainty

- The organizational objective that the risk relates to, and

- The status of the risk assessment: identification, analysis, or evaluation.

The risk registry is central to risk management. Merely having a risk registry is valuable to the organization. Over time, we will refine each risk during the risk analysis phase.